‘Talented fighters are lazy!’: uncovering selection bias in combat sports

Published:

In combat sports like boxing or mixed martial arts, there is a saying that talented athletes lack work ethic compared with less talented ones. As if athletes with the most “raw talent” had a natural tendency to become lazy over time and work less than athletes that were not as gifted with natural “raw talent”.

As a young athlete, I used to believe that too. While nobody is great at first, some athletes learned techniques and moves more quickly than others. In turn, those athletes deemed more naturally talented also seemed to take more time off between competitions and be less willing to go the extra mile. Could it be that, upon realization that they were naturally talented, some athletes thought that they did not have to work as much as others to have competitive success? Are talented athletes doomed to become lazy? Or…

Could there be an alternative explanation?

Most of my research was oriented towards nutritional epidemiology during my PhD. Identifying and learning about source of bias became an important aspect of my work. I now realize that there might be an easy explanation for the observation that “talented fighters are lazy”. This explanation strikes me as a perfect example of selection bias (or, more precisely, collider-stratification bias). This bias is very common, but it is also counter-intuitive which makes it hard to spot.

An informal description of collider-stratification bias

(Very) informally, collider-stratification bias is a bias, i.e., a spurious association, that occurs when focusing on one thing that is caused by other things. When we focus on the one thing, a spurious association is created between the other things. I know this sounds more confusing than anything else.

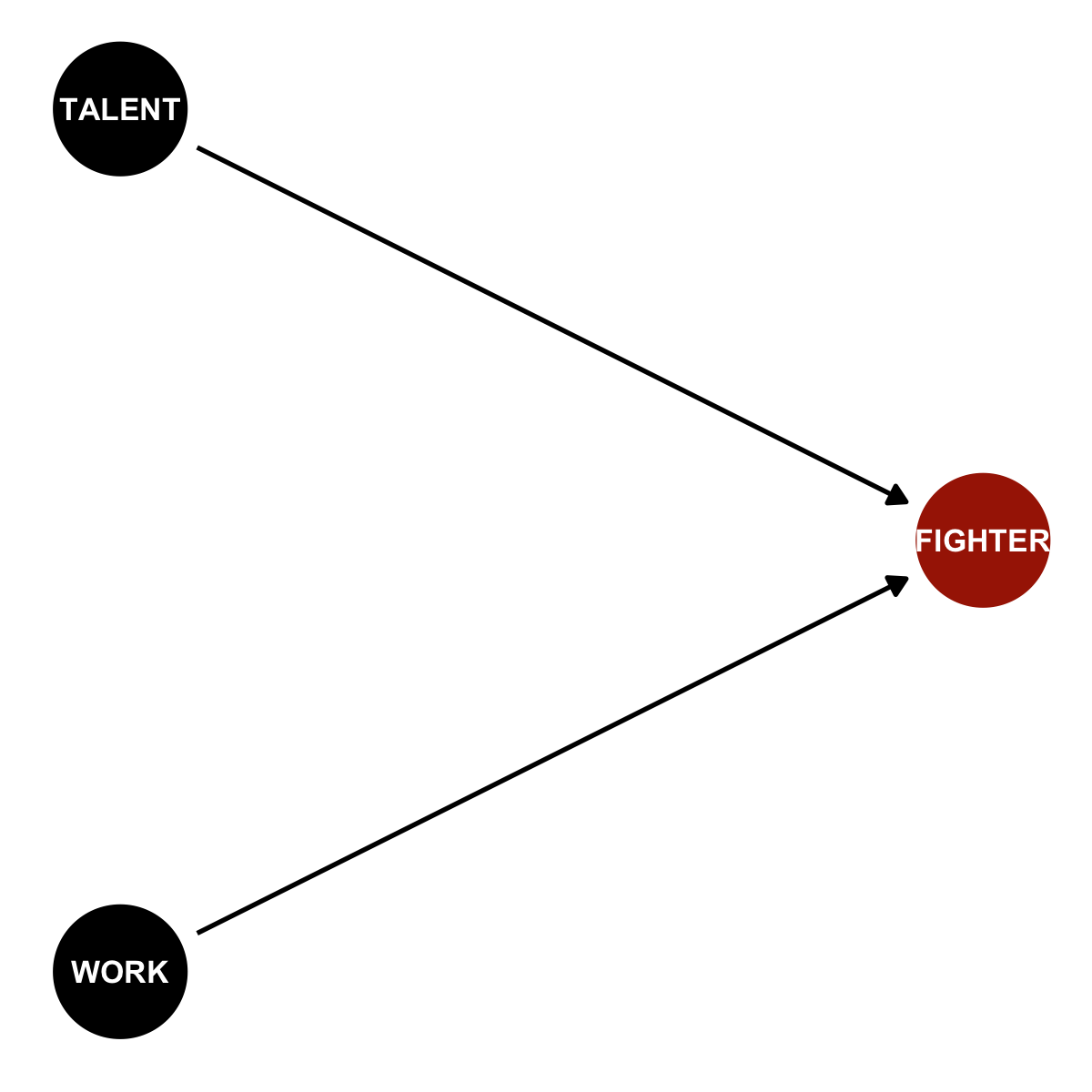

Say that for a combat sport practitioner to step in the ring one day (be a FIGHTER), the practitioner has to have a mix of TALENT (e.g., natural athletic abilities) and WORK ethic (e.g., never miss practice). This is depicted in the figure below, a causal graph. Both TALENT and WORK contributes to and causes one to become a FIGHTER.

Assuming that my causal graph is correct, FIGHTER is a collider: both arrows from TALENT and WORK collide into being a FIGHTER. Considering only those that step in the ring is - in epidemiological jargon - defined as conditioning on FIGHTER (or stratifying by FIGHTER). Indeed, among all people that walk through the gym doors, we unconsciously condition (or stratify) for individuals that become FIGHTER. It is indeed easier to remember individuals that spent months and years training and competing rather than others that only practiced for a short period. And this is the key to collider-stratification bias! Fighters are not a sample of individuals representative of all the population in terms of natural talent and work ethic. I will come back to this point in the next sections.

Of note, one nuance in the graph is that there is initially no relationship between TALENT and WORK. In other words, I assume that work ethic does not cause talent and vice versa. For example, the fact that an individual has a high proportion of explosive muscle fibres (a genetic factor potentially contributing to perceived talent) does not affect one’s work ethic based on my graph. For the purpose of this example, it is a plausible assumption that whatever genetic factors contribute to natural raw talent is not something that should cancel work ethic. On the contrary, if talent affected one’s work ethic (TALENT->WORK), it could even push to work more (“Oh I’m good at this!”->“Let’s do more”). Again, for the purpose of this example, we will assume this does not happen. Inversely, work ethic cannot affect one’s genetic.

What is the impact of collider bias?

Using the model above, I can run a very simple simulation to show that, once we focus only on those that become FIGHTERS, TALENT will appear negatively correlated with WORK. In other words, we may have the impression that natural talent causes athletes to lack work ethic. In reality, this effect does not exist and is a perfect example of collider bias!

# Set R seed to reproduce these results

set.seed(1234)

# Our simulation includes 1000 people (e.g., 1000 gym members)

n <- 1000

# Among those, 100 people (or only 10%) will actually become fighters (i.e., step in the ring)

p <- 0.1

# Simulating that TALENT and WORK are both independent and randomly distributed attributes in our population

talent <- rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = 1)

work <- rnorm(n, mean = 0, sd = 1)

# Among ALL the practitioners, is natural "talent" correlated with "work" ethic?

corr_talent_work <- cor(talent,work,method = "spearman")

corr_talent_work

[1] 0.06188338

In the simulation above, and based on all 1000 individuals, natural talent has a weak correlation of +0.06 with work ethic.

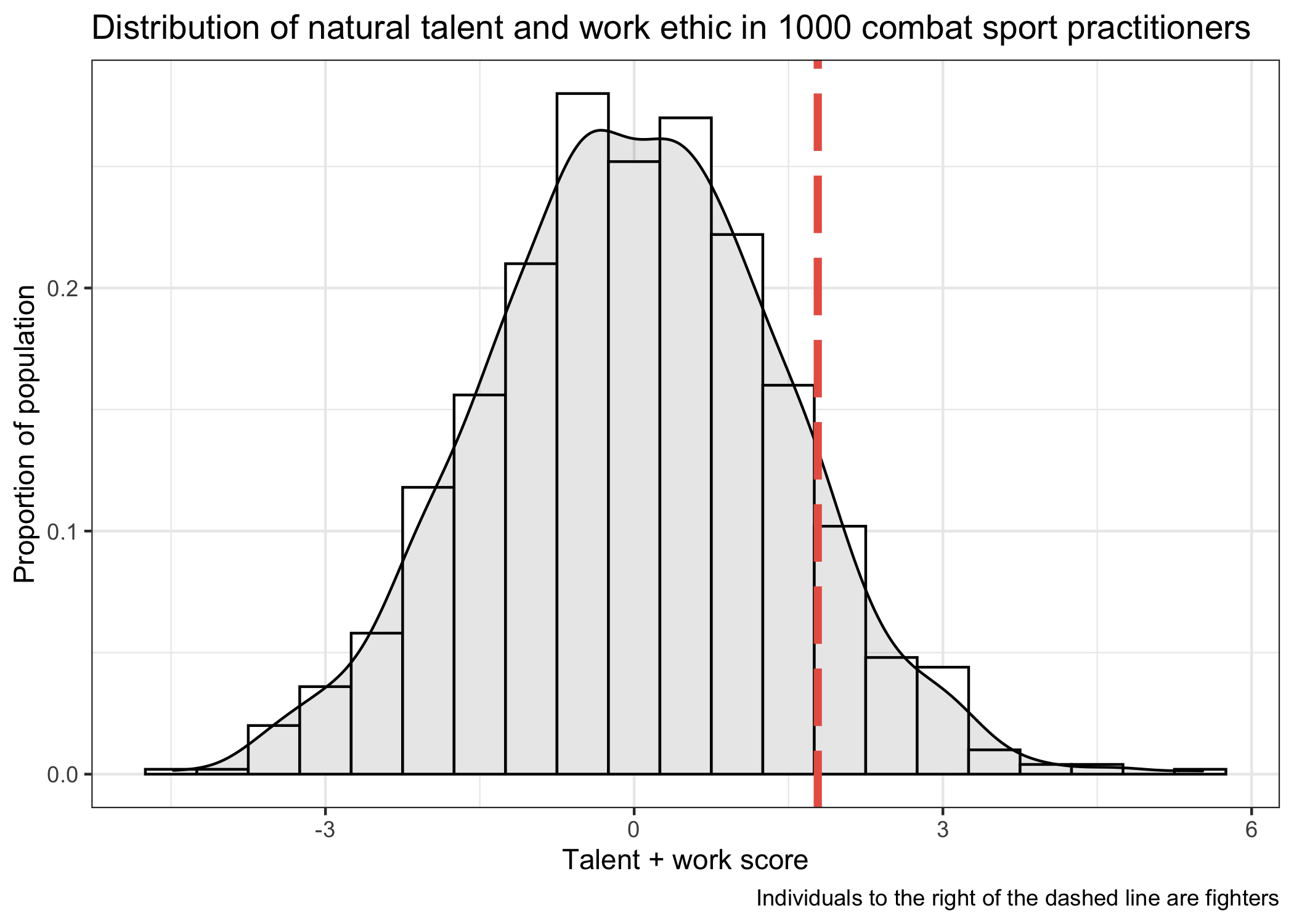

In the next code section, I combine both talent and work score in total. Then, individuals in the top 10% of combined total score are selected.

# Combine both "talent" and "work" into one single metric

total <- talent+work

## note: we now have a 1000 individuals with varying degree of "talent" and "work"

# Combine the variables (talent, work, total) into a single data

population <-

data.frame(

talent = talent,

work = work,

total = total )

# Remember that only 10% (p) athletes become fighters. Based on the "total" variable,

# this means that fighters must have a talent+work total score of at least ...

cut_off <- quantile(total,1-p)

cut_off

90%

1.784185

# Visualize this cut-off

ggplot(data=population,aes(x=total),stat="identity") +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 0.5, aes(y=..density..), colour="black",fill="white") +

geom_density(kernel="gaussian",fill="black",alpha=0.1) +

geom_vline(xintercept=cut_off,colour="#e76254",

linetype="longdash",size=1.5) +

labs(title = paste0("Distribution of natural talent and work ethic in ", n,

" combat sport practitioners"),

x="Talent + work score",

y="Proportion of population",

caption="Individuals to the right of the dashed line are fighters") +

theme_bw()

# Stratification: identify the top athletes that will step in the ring

population$fighter <-

ifelse( population$total >=cut_off, TRUE,FALSE)

## Confirm that only "p" individuals are actually fighters

table(population$fighter)

FALSE TRUE

900 100

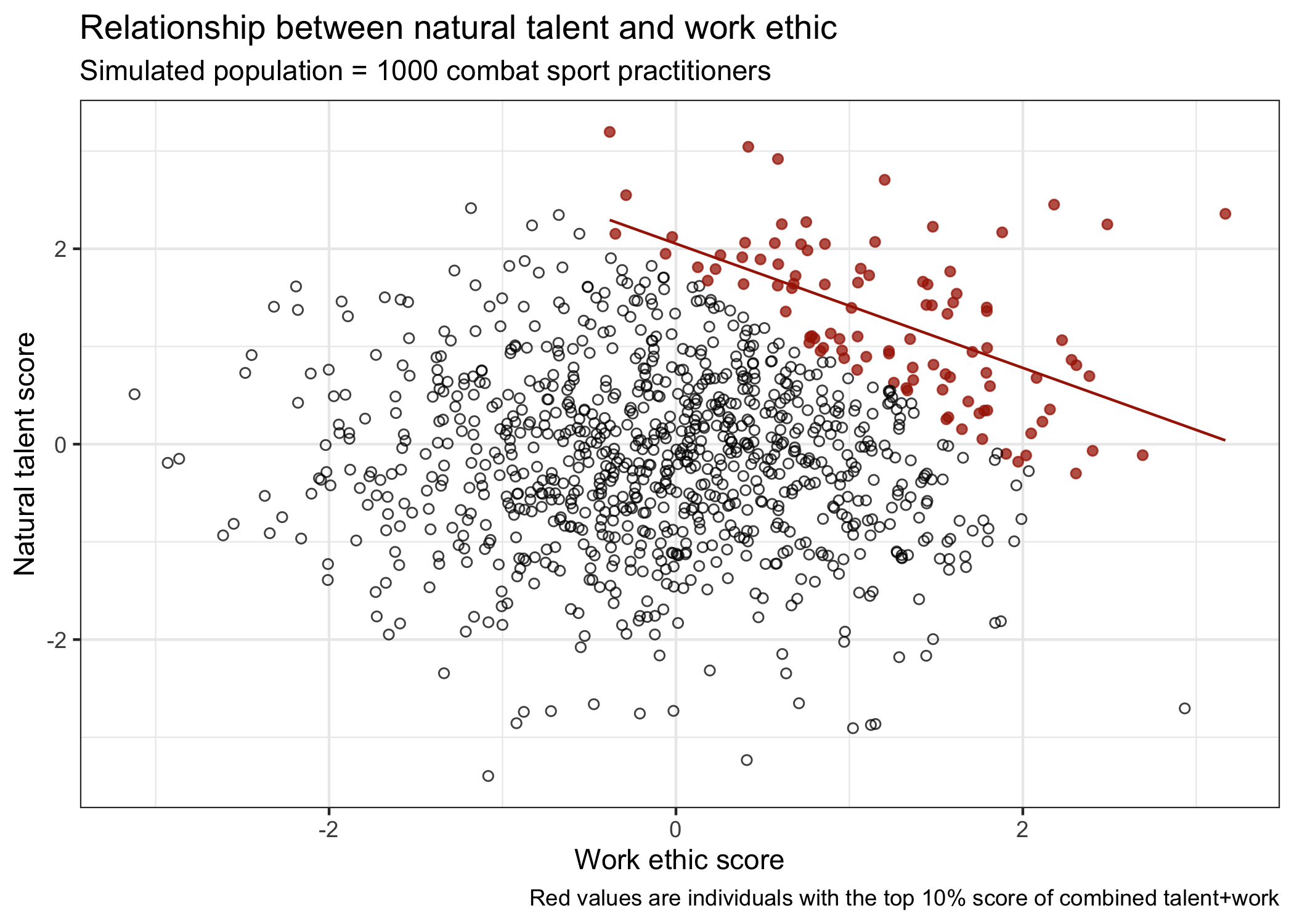

Now, we can look at the correlation between talent and work in the top 10% individuals sample based on their total talent + work score.

# Select only fighters (i.e., condition/stratify), calculate correlation

corr_among_fighters <-

population |>

dplyr::filter(fighter==TRUE) |>

dplyr::select(talent,work) |>

cor(method = "spearman")

# And the correlation is ...

corr_among_fighters[1,2]

[1] -0.6007201

In our sample of fighters, the correlation between TALENT and WORK is -0.60! Recall that, in our full population, the same correlation was almost 10-time weaker (0.06). Clearly, when looking only at fighters, i.e., the top athlete that will eventually step in the ring, natural TALENT seems negatively correlated with WORK ethic. The common interpretation is that talent somehow causes fighters to be lazy. However, this effect does not exist.

Conclusion

The explanation is rather simple. Given that individuals in our population are a combination of talent and work, it happens more often that fighters will either have a lot of natural talent OR a great work ethic. Since it is less frequent that fighters will score high for BOTH attributes, talent and work will appear inversely correlated in fighters. In other words, fighters (the top 10% athletes in our population) more frequently have great natural talent OR great work ethic, but less frequently have great natural talent AND great work ethic at the same time. In real life, more than 2 things contribute to one’s ability to compete in combat sports. The bias is not expected to be as large as in the simulation, but it can probably explain some of the perceived relationship.

# Visualize the bias in our population

ggplot(data=population,aes(x = work, y = talent, color = fighter)) +

geom_point(aes(shape = fighter), alpha = 3/4) +

geom_smooth(data = population |> filter(fighter == TRUE),

method = "lm", fullrange = F,

color = "#A82203", se = F, size = 1/2) +

labs(

x = "Work ethic score",

y = "Natural talent score",

title="Relationship between natural talent and work ethic",

subtitle = paste0("Simulated population = ",n," combat sport practitioners"),

caption = paste0("Red values are individuals with the top ",p*100,"% score of combined talent+work")

) +

scale_color_manual(values = c("black", "#A82203")) +

scale_shape_manual(values = c(1, 19)) +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.position = "none")

There are tons of other examples of collider bias in real life (e.g., handsome men are jerks!); nice examples are presented on Twitter at this link.

Reference

Kurz, S (2021). Statistical rethinking with brms, ggplot2, and the tidyverse: Second edition - The Haunted DAG & The Causal Terror. Available at: https://bookdown.org/content/4857/the-haunted-dag-the-causal-terror.html